Antique spinning wheels can be much more than primitive country décor. For a handspinner, they make excellent options to buying a modern wheel. However, a lack of knowledge leads to overpriced wheels that lanquish in antique stores or on Ebay and Craigslist. Learning what to look for in an antique wheel results in fairly priced wheels that quickly find new homes with handspinners who return them to a useful life.

The first thing to consider is the style of the wheel and what it was used for. Handspinners wince or laugh when they see a great wheel listed as a “flax wheel” or a skein winder listed as a spinning wheel. They will groan when the price is so unaffordable as to be outlandish. Fortunately, the internet is a convenient source of information and a quick Google search can provide guidance for a seller or new handspinner in determining what a wheel actually is, the type of fiber spun on it, and a fair price range.

At a very high level, there are two basic wheel styles – the bench wheel and the upright wheel. Bench wheels include the great or walking wheel and the smaller Saxony, the style of which most people equate to the stereotypical spinning wheel. Upright or parlor wheels have their drive wheel above, below, or behind the flyer, instead of on opposite ends of a bench. These wheels, also called travelling wheels, were designed to take up less space and be more portable than the bench or great wheels.

Bench wheels come in varying styles other than the aforementioned Saxony, including the split or straight bench style of some Norwegian wheels or the so-called “slanty” wheel with its steeply pitched bench. These wheels typically are treadle driven. The great or walking wheel has no treadle; the spinner stands to spin the flat-rimmed drive wheel. These wheels spin fiber off of a spindle tip, as opposed to the flyer assembly on a treadle-driven wheel.

Great wheels are also known as “wool wheels,” as this was the principle fiber spun on this style. Treadle wheels with a very small orifice were typically used for spinning flax. The larger treadle wheels with cast iron tensioning and treadle were designed to be wool wheels, although any fiber can be spun on them.

Finding an antique wheel is not too difficult; finding one that spins can be a challenge. To a spinner, the most annoying Craigslist posting is the one that pictures a wheel, obviously missing key parts, yet boasting a caption that says, “It works!” When questioned, most sellers will innocently say they believe the wheel works because “…it goes around.” Unfortunately, there is much more to a workable spinning wheel.

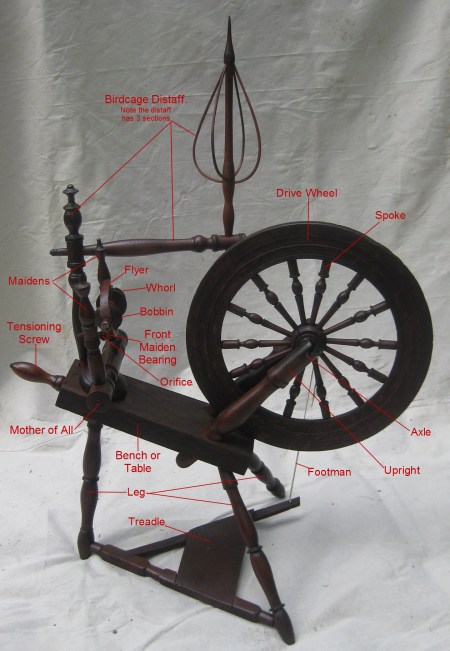

No matter the style, the wheel’s price should be dictated primarily by the presence and condition of its original parts. These may be categorized as: the flyer assembly and mother-of-all (MOA), the drive wheel, and the overall body structure.

The flyer assembly and MOA sit at the opposite end of the bench from the drive wheel. This includes 1.) the tensioning screw or tilt tension mechanism, 2.) the MOA, 3.) the maidens (the uprights that support the flyer), and 4.) an assembly consisting of the flyer, bobbin, and whorl. These parts are among the most expensive to repair or replace, so a considerable percentage of the purchase price is centered here.

The wooden knob at the end of the bench is attached to a long wooden screw-turned shaft. This shaft screws through the center of the MOA mount. The screw should turn easily and move the mount forwards or backwards. This aids in tensioning the wheel’s driveband for spinning. Before turning the tensioning knob, inspect the bench top for a small peg that might be inserted alongside the tensioning screw. This is a retaining pin to prevent the tensioning screw from slipping; it should be tapped out from the bench’s underside to prevent splitting or stripping the wooden screw. A tensioning screw that is damaged or missing can be a fatal flaw, as it is nearly impossible to turn a new one with threads to match the MOA threading.

Wheels from the latter half of the 19th and early 20th century, particularly those manufactured in Canada, introduced “tilt tensioning.” Typically made of cast iron, but often as simple as a U-bolt or carriage bolt, a tilt tensioning system allowed the spinner to adjust the driveband tension by loosening or tightening a wing nut to tilt the MOA backwards or forwards.

The MOA itself should be sturdy, with no wobbles. The threaded base for the tensioning screw fits tightly into the MOA base; the MOA crossbar should fit snugly on the base. A MOA that is loose or falling apart will not support the flyer assembly for spinning. Cost to repair the MOA using existing pieces typically costs between $50 and $100, depending on the severity of the problem. Lathing new parts would add to this cost.

The maidens consist of wooden uprights with leather bearings that support the flyer assembly. Maidens should fit snugly in the MOA crossbar. The front maiden, the one that supports the flyer orifice, should turn relatively easily towards the spinner to allow for release of the flyer. Maidens that are very loose may be shimmed with a small piece of glove leather. Damaged or missing bearings are easily replaced with tooling leather or even a section of old belt. Cracks or chips should not interfere with spinning ability. Missing maidens can be replaced by a competent wood turner, but this will drive up the end cost of the wheel.

The flyer assembly, consisting of the flyer, bobbin, and whorl, accounts for possibly the largest percentage of your purchase price. The flyer is the “business end” of the spinning wheel; it is where the fiber is spun into yarn and it is what winds the finished yarn onto the bobbin. The whorl and bobbin may be chipped, but must be present for the assembly to be considered complete. A flyer that is obviously not the original will also decrease the wheel’s value.

A missing flyer assembly will cost upwards of $200 to replace. The metal flyer shaft is costly to replace, as it requires a craftsman with a metal lathe to turn a new one. A flyer that is missing an arm, shows evidence of an old mend, or has missing or rusted hooks is worth less than a flyer in pristine condition. If the metal shaft is present, the flyer and hooks can be replaced at less cost than having the whole assembly remade; typically, it should cost under $100 to replace just a broken flyer using its own metal shaft.

An existing but mended flyer should be evaluated carefully. The pressure of the drive band and momentum of spinning put a tremendous strain on the flyer. Spinners related stories of flyers losing an arm in mid-spin, creating a dangerous projectile that can travel fast enough to dent wallboard. A clumsily repaired flyer will need to be rebuilt to make it safe for spinning.

The bobbin is a wooden tube with end caps that fits over the flyer shaft. One end of the bobbin should be rounded, or have a plain wooden disc, that faces the wooden flyer. The top of the bobbin should have either a groove around the edge of the end disk, or a secondary disk on top. This holds the driveband in place around the bobbin.

The whorl is a single- or double-grooved wooden disk that typically screws onto the flyer shaft or, with some European wheels, has a friction fit. WARNING: be very careful when attempting to unscrew a whorl. They often are threaded in the opposite direction from modern threading and will not tolerate much pressure in unscrewing. A stubborn whorl will disintegrate into wood chips when forced. A few drops of WD40, given time to sink in, usually coaxes a stubborn whorl to unscrew. The whorl holds the second loop of the drive band in place on a double drive wheel. It should be relatively free of chips and cracks, and the center screw piece should not turn independently of the wood.

A great wheel has a spindle rather than a flyer assembly. The MOA and maidens support a long metal spindle, typically with a wooden whorl on its shaft and possible a wooden or leather disc to prevent fiber from winding on past a certain point. A more advanced set-up includes a large whorl known as a “minor’s head”; this is an accelerating device that mounts on the top of the MOA and acts as a second wheel to turn the spindle faster. Replacing the entire MOA, spindle and miner’s head can cost over $100, so evaluate carefully.

At the opposite end of the spinning wheel bench, the drive wheel represents another large percentage of the wheel’s price. The drive wheel should be true and turn without warp or wobble. It should have all its spokes. The axle crank should fit snugly through the center of the wheel hub and should not turn independently of the wheel. The hub should be free of cracks, as should the wheel rim. The wheel rim may have expansion joints and these might have small spaces in between each; these spaces are not fatal flaws, as they allow for the wood to expand and contract with heat or cold. However, should the joins be cracked, sprung, splintered, or glued, these could all affect its ability to spin smoothly. The drive wheel should also line up with the flyer’s whorl and bobbin.

The bench should be carefully inspected for flaws or old repairs. It should be structurally sound; a hairline fracture could indicate a potentially splitting problem. The legs should fit snugly; inspect them to see if they are pegged or nailed into place. A wooden peg may have been inserted by the maker, but a nail or worse, a screw, might indicate a leg that kept falling out.

Uprights should likewise fit snugly and should not be split or broken where the drive wheel is inserted. Metal, or sometimes bone, bearings should be present to support the wheel axle and prevent its wearing against the wood. A small hole in the rear of the upright may indicate a missing secondary support, although not all wheels carried these.

The bench should be inspected for holes and marks. Holes in the bench could indicate a missing distaff, reeling pin, or orifice hook. Maker’s marks were often stamped in the end grain of the bench or stenciled on top.

Pricing a wheel can be tricky, especially for those uninitiated in spinning wheels. A wheel that is broken or missing major parts should typically cost under $100, depending on the severity of damage. A wheel in spinning condition with all its working parts could run anywhere between $100 and $200, depending on the style, the maker, and the condition. A wheel with minimal damage but in “barn-fresh” condition will be worth less than one that has been cleaned and restored to a pristine finish. A wheel with its original pristine finish will be worth even more.

Generally, a buyer on the East Coast can find a nice wheel that requires minimal restoration in the $100 to $200 range, including great wheels. Common wheels that turn up priced in the thousands are unrealistic. Good references such as the books by Joan Cummer, Patricia Baines, or Pennington & Taylor will provide a more realistic view of what a wheel is worth, given its condition and availability. Some wheel styles are less common in other areas of the country and this could affect pricing, but not so steeply that the wheel becomes unaffordable.

A true “working” wheel needs to have much more than just a drive wheel that turns. It needs an undamaged, unwarped drive wheel that sits smoothly in its uprights. It requires a structurally sound body and legs. Most importantly, it requires a complete flyer assembly and tensioning system, or spindle in the case of a great wheel, with a minimum of cracks and flaws. A wheel needs to be evaluated based on missing or broken parts and the availability of having these remade. Should the cost of restoration exceed the asking price of the wheel, the wheel is not fairly valued and should be repriced accordingly.

Posted by thewoolmerchantsdaughter

Posted by thewoolmerchantsdaughter

You must be logged in to post a comment.